"We’ve pulled the stars from the skies and brought them down to Earth, but at what cost? When we turn on all these lights, we’ve lost something precious…the stars.." - Neil DeGrasse Tyson

For most of human history, the phrase "light pollution" would have made no sense. Imagine walking toward London on a moonlit night around 1800, when it was Earth's most populous city. Nearly a million people lived there, making do, as they always had, with candles and rushlights and torches and lanterns. Only a few houses were lit by gas, and there would be no public gaslights in the streets or squares for another seven years. From a few miles away, you would have been as likely to smell London as to see its dim collective glow.

Now most of humanity lives under intersecting domes of reflected, refracted light, of scattering rays from overlit cities and suburbs, from light-flooded highways and factories. Nearly all of nighttime Europe is a nebula of light, as is most of the United States and all of Japan. In the south Atlantic the glow from a single fishing fleet—squid fishermen luring their prey with metal halide lamps—can be seen from space, burning brighter, in fact, than Buenos Aires or Rio de Janeiro.

In most cities the sky looks as though it has been emptied of stars, leaving behind a vacant haze that mirrors our fear of the dark and resembles the urban glow of dystopian science fiction. We've grown so used to this pervasive orange haze that the original glory of an unlit night—dark enough for the planet Venus to throw shadows on Earth—is wholly beyond our experience, beyond memory almost. And yet above the city's pale ceiling lies the rest of the universe, utterly undiminished by the light we waste—a bright shoal of stars and planets and galaxies, shining in seemingly infinite darkness.

Light pollution is a detriment not only to astronomers, but also to human beings and all the animals, plants, and insect life with which we share our planet. Finding a truly "dark sky" is almost unheard of for most Americans. In many cases, it requires driving hours from major cities and towns to remote rural areas and even then it can be tricky. Most children grow up today never realizing that there is a night sky shimmering and glowing with wonders beyond belief, accessed as simply as looking up, but impossible to see due to poorly implemented and over-utilized artificial light.

Bee Sting Hill Observatory is located in the relatively dark skies of Northeastern Georgia. While the sky here is comparatively dark and good for astronomy, it is still a far cry from the darkest skies available. To help monitor light pollution and determine the best nights for observing, I've recently setup a Sky Quality Meter (SQM) at my observatory. The graphs below provide real-time readings of sky darkness in my area.

For most of human history, the phrase "light pollution" would have made no sense. Imagine walking toward London on a moonlit night around 1800, when it was Earth's most populous city. Nearly a million people lived there, making do, as they always had, with candles and rushlights and torches and lanterns. Only a few houses were lit by gas, and there would be no public gaslights in the streets or squares for another seven years. From a few miles away, you would have been as likely to smell London as to see its dim collective glow.

Now most of humanity lives under intersecting domes of reflected, refracted light, of scattering rays from overlit cities and suburbs, from light-flooded highways and factories. Nearly all of nighttime Europe is a nebula of light, as is most of the United States and all of Japan. In the south Atlantic the glow from a single fishing fleet—squid fishermen luring their prey with metal halide lamps—can be seen from space, burning brighter, in fact, than Buenos Aires or Rio de Janeiro.

In most cities the sky looks as though it has been emptied of stars, leaving behind a vacant haze that mirrors our fear of the dark and resembles the urban glow of dystopian science fiction. We've grown so used to this pervasive orange haze that the original glory of an unlit night—dark enough for the planet Venus to throw shadows on Earth—is wholly beyond our experience, beyond memory almost. And yet above the city's pale ceiling lies the rest of the universe, utterly undiminished by the light we waste—a bright shoal of stars and planets and galaxies, shining in seemingly infinite darkness.

Light pollution is a detriment not only to astronomers, but also to human beings and all the animals, plants, and insect life with which we share our planet. Finding a truly "dark sky" is almost unheard of for most Americans. In many cases, it requires driving hours from major cities and towns to remote rural areas and even then it can be tricky. Most children grow up today never realizing that there is a night sky shimmering and glowing with wonders beyond belief, accessed as simply as looking up, but impossible to see due to poorly implemented and over-utilized artificial light.

Bee Sting Hill Observatory is located in the relatively dark skies of Northeastern Georgia. While the sky here is comparatively dark and good for astronomy, it is still a far cry from the darkest skies available. To help monitor light pollution and determine the best nights for observing, I've recently setup a Sky Quality Meter (SQM) at my observatory. The graphs below provide real-time readings of sky darkness in my area.

|

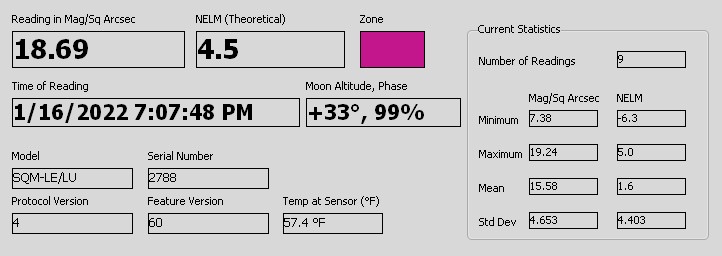

This image (updated live) shows the last reading taken by the Sky Quality Meter (SQM). The reading is shown in Magnitude per Square Arc-second, which is a standard for measuring night sky brightness. It also shows the Naked Eye Limiting Magnitude (NELM), which implies the theoretical limit for the darkest objects one could see with the naked eye.

|

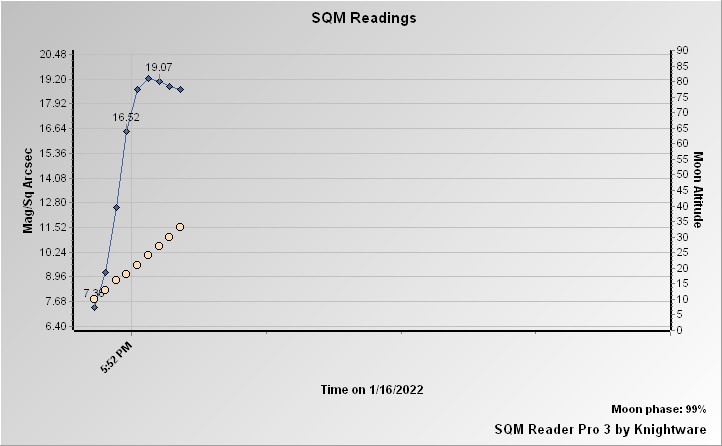

This graph shows the real-time Magnitude per Square Arc-Second measurement. The graph is updated every 15 minutes and includes current moon phase and moon altitude. Any reading greater than 20.00 is considered a relatively dark sky. The readings are affected by weather and clouds, which reflect more light back to the ground. Additionally, the moon altitude and phase plays a large role in the overall darkness of the sky.

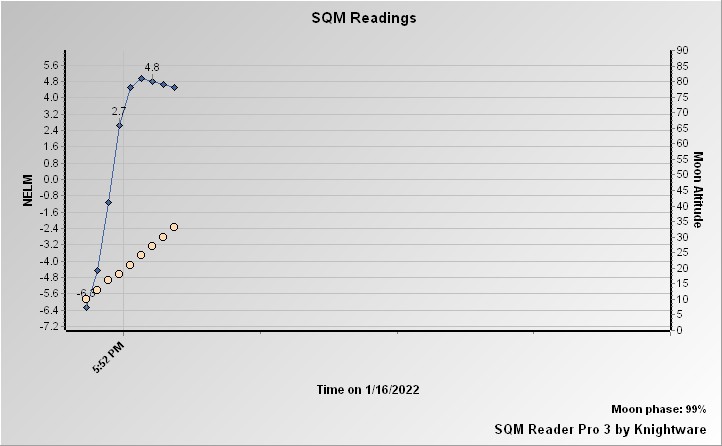

This graph shows the Naked Eye Limiting Magnitude (NELM). This value represents the theoretical darkest sky objects that you could see on a clear night based on the amount of light pollution and sky brightness level. The area the observatory is in typically experiences NELM values of 5.8-6.1 based on time of night and clarity of the sky. Being in close proximity to the town of Blue Ridge has the greatest impact on the darkness of the sky, even though Blue Ridge is a very small town with a light pollution ordinance. A value of 6.0+ is considered a reasonably dark sky. Big cities such as Atlanta experience values closer to 2.0-2.5, which limits the sky to only the very brightest objects.